Education Systems and Systemic Racism

We generally try to keep a more broad international focus, but this post focuses on the education system in the United States of America. Discussions of systemic racism and systemic inequality in education are useful to at least some extent everywhere, but the specific policies and practices I reference here are American.

By Katie Caves

It is impossible to ignore the current movement calling for an end to systemic racism. We know that equity—on dimensions like race, gender, family background, and religion—is an issue in every education system. The problem is huge, amorphous, and intimidating. Social scientists have worked and continue to work on identifying the sources and effects of systemic bias. We’re clearly not doing enough.

People are sharing and consuming huge amounts of information on systemic racism right now, and the discourse is jumping ahead in leaps and bounds. I’ve recently seen excellent resources on systemic racism from sources like external pageBen & Jerry’scall_made (yes, as in ice cream). Their piece on systemic racism in education outlines issues like the school-to-prison pipeline, lingering segregation, and the unequal distribution of student debt. Widely shared external pagevideos like this onecall_made deal with issues like redlining, the intergenerational transmission of wealth, and school funding. Topics I wasn’t fully aware of until grad school are the subject of heated twitter arguments.

Fixing broken systems is complicated because there are observable problems on every level from the classroom to the Department of Education, from pre-kindergarten to post-graduate, and from the first class in the morning to last class of the day. Knowing where to start—finding the right point of leverage—is not a trivial issue. The solution is likely not just one but many different solutions acting on specific problems.

The nature of looking at education from a systems perspective is that we generally do not start with individual interactions. Teachers and school leaders are buffeted by the system just as much as their students are, with incentives set far above them and limited options for action. Even districts operate within constraints like funding or state- and federal-level incentives. We work at the system level in an effort to prevent problems upstream and enable improvement.

In the conversation on systemic racism in education, the key emerging policy priority is ending the American practice of funding schools from local property taxes. Funding in this manner external pageoriginates from and perpetuates structural racismcall_made in education, and leads to external pagemassive and measurable differences in the resourcescall_made available to white American students and American students of color. Fixing this issue is a clear necessity, the kind of intervention that enables other efforts like program improvements and school finance equity to work.

There is another foundational source of systemic racism that’s not just about having access to things but is also about having something to access. Let’s take a look at what this means.

If I were to imagine a maximally inequitable system of education, it would be one where there is one pathway to success, where all students are aiming for the same goalposts. That pathway would have space for less than half of all students. The goalposts and the route to them would be built by and for those with privilege, and it would be expensive. Students who fall off the pathway or fail to reach the goalposts would have no clearly defined alterative pathway to success (except for finding a way back onto the main pathway), and when alterative pathways exist they would be small, difficult to access, or would require connections that tend to be associated with privilege.

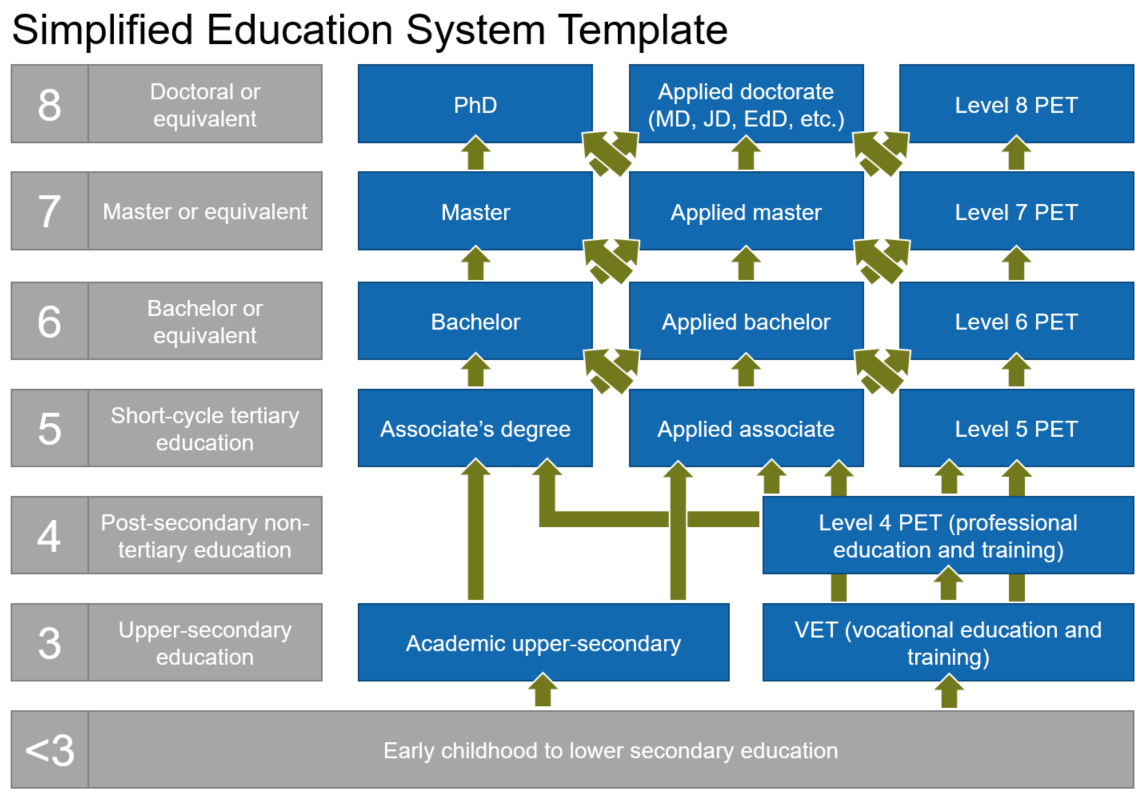

I can show a simplified version of any education system using the external pageInternational Standard Classification of Education (ISCED)call_made. There are 8 levels in ISCED, but I’ll focus on the ones that start around age 15 or 16, from level 3 onward. From there up, programs can be academic (on the left), applied (middle), or vocational/professional (right) at any level. An example system with a program at every possible place and connections between all of them (in green) would look something like this:

Notes: The programs listed in each box are examples and are not the only type of program that can exist in those boxes. Green arrows indicate direct progression. Programs are organized by ISCED level vertically and from left to right by academic, applied, and vocational/professional. PET stands for professional education and training.

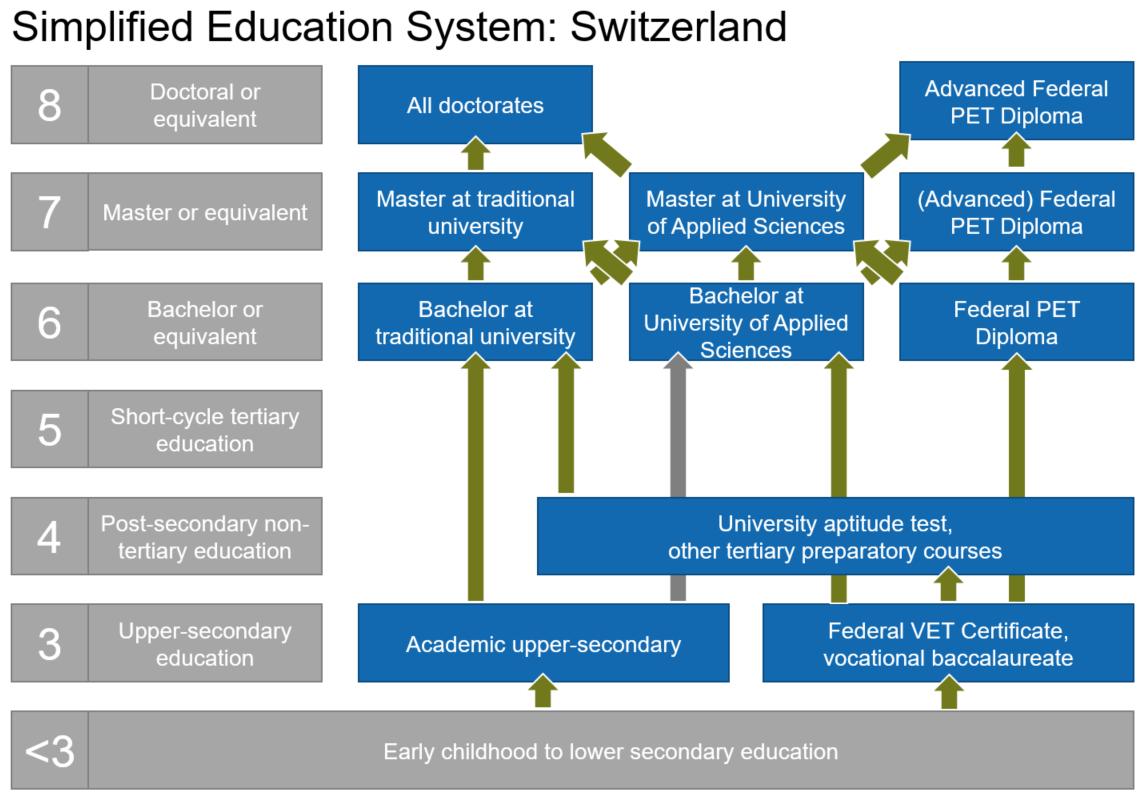

I used the official external pageISCED-mapped programscall_made to put systems into the same format. While there isn’t a country that lists programs in every possible level and type, the Swiss system comes close.

Notes: Based on ISCED mappings and more up-to-date information from the external page2018 Swiss Education Report.call_made The programs listed in each box follow the ISCED mapping of the Swiss system. Green arrows indicate direct progression, grey indicates progression with additional requirements. Programs are organized by ISCED level vertically and from left to right by academic, applied, and vocational/professional. VET stands for vocational education and training, and PET stands for professional education and training.

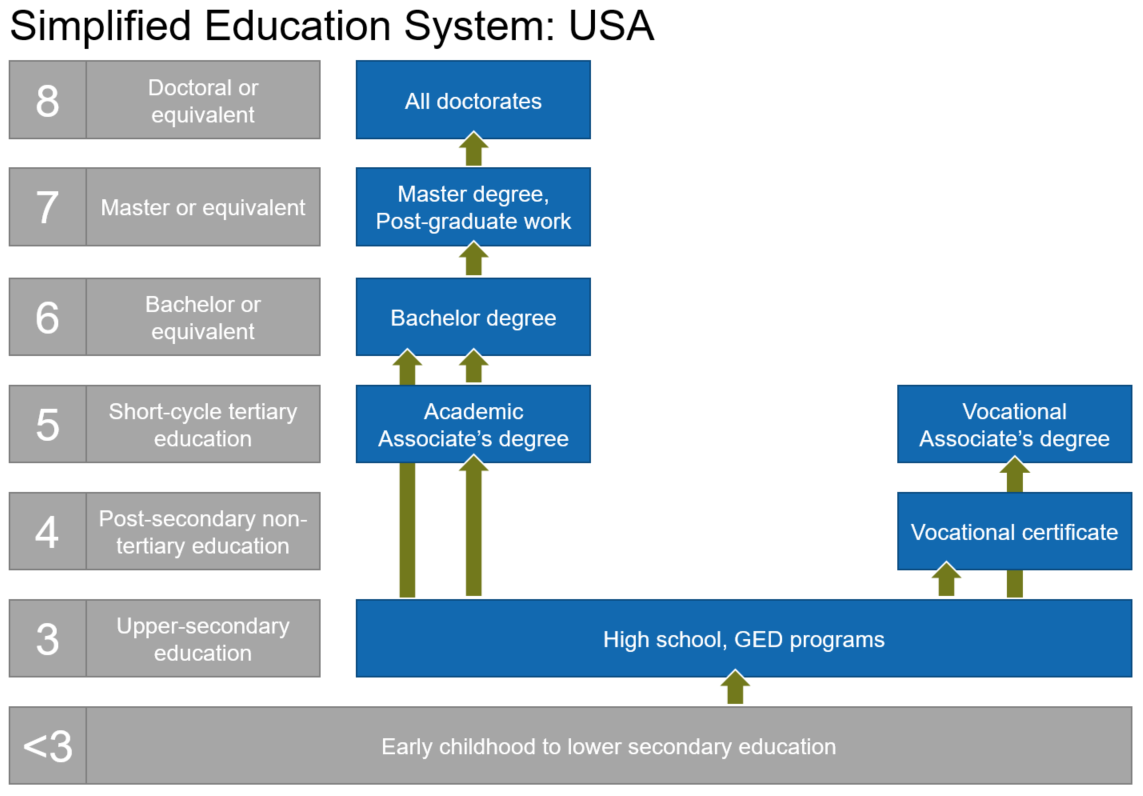

When I look at the official ISCED mapping for the United States, there’s a clear difference:

Notes: The programs listed in each box follow the ISCED mapping of the American system. Green arrows indicate direct progression. Programs are organized by ISCED level vertically and from left to right by academic, applied, and vocational/professional.

This picture shows the maximally inequitable model I described earlier, which has a lot in common with the American education system. The one pathway to success is college. Other programs exist, but they either set students up for failure or require failure as a condition of entry. For example, the vocational associate’s degree does not offer any options for further education and training—where should those students find higher-level professional skills? As another example, Registered Apprenticeship is operated by the Department of Labor and lies outside the education system, so students don’t have a clear path into or out of the program. Although individuals external pagecan start the Registered Apprenticeship at age 16 or 18call_made, the average age of a Registered Apprentice is late 20s. That long gap between finishing high school (a program requirement) and starting a basic training program implies a long period of struggling.

From inside the American education system, college feels like the only possible option and the only way to help students achieve success—or at least livable wages. Add in the segregationist history of “Voc Ed”—past vocational education programs in the United States—and it can seem frankly insane to bring up the words “vocational education” in a conversation about dismantling systemic racism1. That is for other people’s children2. But there are at least two crucial differences between the vocational and professional education and training we find in the vast majority of national education systems and the Voc Ed of the past: pathways up and pathways across.

Any education program that doesn’t offer a way to the top of the education system is a dead end. Looking at the American offerings on the vocational/professional side of the map, it’s clear that these fit that description. Vocational students may find a way to access academic education, but that happens despite the system, not because of it. The labor market demands and rewards high-level professional skills, but young Americans have no way of formally attaining those skills. Young people without the connections to access internships, traineeships, and mentors are even more at a disadvantage.

Similarly, if a pathway is disconnected from the rest of the education system, it prevents students from changing course and makes them more vulnerable to economic shocks. This increased risk makes narrow or closed-off programs unattractive, which creates a second class of education. When students in vocational education and training programs can’t access academic higher education, the vocational programs are less attractive and only populated by those who cannot access academic higher education. Social stigma against vocational education is an outcome of the program’s quality and connection to further opportunities, not the other way around.

I’ve talked about the importance of a permeable education system before on this blog. The important point is that permeability isn’t just about access, it’s also about opportunities. The American education system can and should offer a lot more opportunity and a lot more types of opportunity than it currently does. Doing this can help it move from a mechanism of systemic racism to the generator of opportunity it is supposed to be. The best teachers, principals and parents in the world cannot help every student under the current system, and the most disadvantaged students are worst affected. Resolving systemic racism in education requires that all students have access to everything, and it also requires that students have something to access.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Oakes, J. (1983). Limiting opportunity: Student race and curricular differences in secondary vocational education. American Journal of Education, 91(3), 328-355.

2 Delpit, L. (2006). Other people's children: Cultural conflict in the classroom. The New Press.