KOF YLMI

The last three blog posts have talked about how we measure one characteristic of good vocational education and training (VET) systems. Through all of that, we’re assuming that linkage is better for something—but what? This post will talk about one way we measure the outcomes of VET systems: the KOF Youth Labor Market Index (KOF YLMI).

By Katie Caves

The last three blog posts have talked about how we measure education-employment linkage as a characteristic of good vocational education and training (VET) systems. We discussed how we identify and measure linkage, which countries have higher and lower scores, and zoomed in on the American state of Colorado to look at some of the key parts of linkage. Through all of that, we’re assuming that linkage is better for something—but what? This post will talk about one way we measure the outcomes of VET systems: the KOF Youth Labor Market Index (KOF YLMI).

Why do we need an index?

One easy way to look at VET-system outcomes is just to check unemployment rates. If we want to be especially focused, we can just look at youth unemployment. However, that can create problems. Unemployment rates are determined by a lot of variables outside of VET. Different governments have different policies about how unemployment should be treated. For example, Nepal’s new constitution has guarantees citizens the right to employment—that might mean that the country would achieve 0% unemployment by placing every potentially unemployed worker in a job of some kind.

Measuring unemployment is also potentially inconsistent. International organizations like the ILO and OECD have their own definitions and collect statistics that meet their standards, but countries can have their own definitions or collect and categorize data in a way that doesn’t compare across countries. If one country considers a worker who has been out of work for two months unemployed regardless of job search activity, another might require them to apply for 15 jobs before they qualify. Statistical stuff like how data is sampled, collected, and treated can make huge differences in the resulting numbers.

Even if every country in the world had perfectly comparable labor policy, unemployment definitions, and statistical methods, it still wouldn’t be a good-enough outcome measure for VET systems. We don’t just want to know whether people have jobs, we also want to know if they are good jobs where workers are treated well and feel secure. We want to know if youth are using the skills they learned to carry out their jobs, and whether they are pursuing further education and training options when applicable to further their careers. Finally, we need to know if young people are able to get jobs quickly and without too many challenges. To answer those questions, we need to measure outcomes on a multi-dimensional index.

What is in the KOF YLMI?

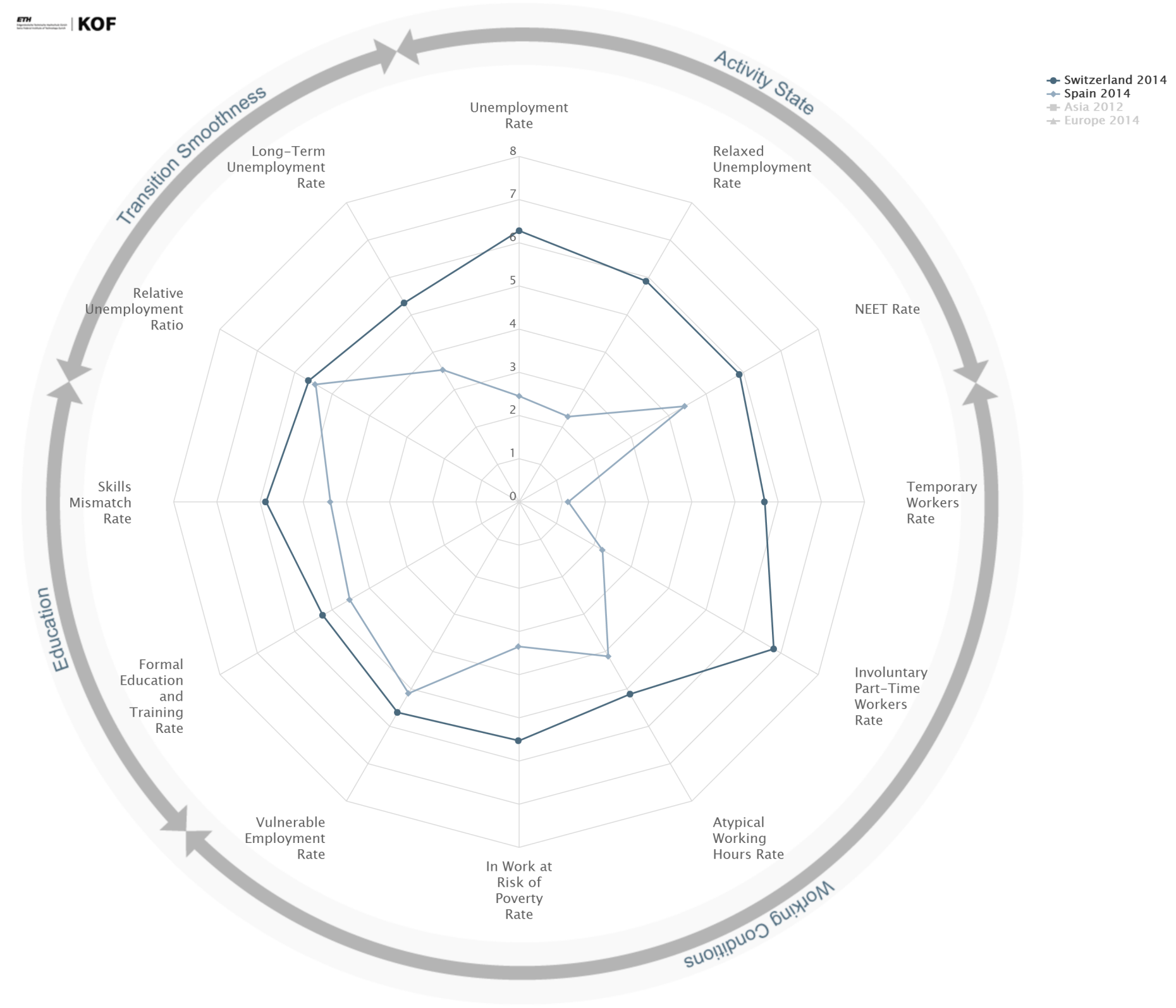

The KOF YLMI looks at young people’s outcomes on the labor market on 12 dimensions that fall into four categories. The dimensions are Activity State, Working Conditions, Education, and Transition Smoothness. Together, the measures in those dimensions address how many young people are working, how good their jobs are, how well prepared youth are for the labor market, and how easily they can find jobs when they look. Every statistics is collected for youth specifically, which is defined as people aged 15-25. Figure 1 shows scores for Switzerland and Spain in 2014, as an example.

Figure 1

Activity State covers all of the measures related to whether young people are able to find work: the unemployment rate, relaxed unemployment rate, and rate of people not in employment, education, or training (NEET). Unemployment is the most obvious statistic, and sometimes the only one used to measure education and training outcomes. Relaxed unemployment covers all young people who are available for work but not working—unlike the normal requirement for unemployment rates, this statistic does not require people to search actively for work. Finally, the NEET rate is people who are not active in the labor market but not doing anything else (like education) either.

Working Conditions covers the quality of young people’s work experiences and opportunities: the temporary workers rate, involuntary part-time workers rate, atypical working hours rate, in work at risk of poverty rate, and vulnerable employment rate. Temporary workers have limited-duration contracts and might lose their jobs. Involuntary part-time workers are available to work full time but cannot find full employment. Atypical working hours cover night shifts and weekends that might affect quality of life. In work at risk of poverty is youth who have jobs but are paid so little they might still not make enough to comfortably survive. Finally, vulnerable employment covers jobs in personal and family businesses, where working conditions can be informal or inadequate.

The Education dimension of the KOF YLMI covers how many young people are prepared to work and how well that preparation matches their eventual working lives. It includes the formal education and training rate, and the skills mismatch rate.

Finally, the Transitions Smoothness dimension measures how difficult it is for young people to enter the labor market: it includes the relative unemployment ratio of young people compared to older adults, and the long-term unemployment rate of young people.

What do we do with KOF YLMI scores?

We don’t just use the KOF YLMI as our outcome variable in studies like the KOF EELI. Part of our research is to track KOF YLMI scores over time and keep the online tool up to date with new statistics and more countries. Currently, the tool covers 178 countries from 1991 to 2014. We add new data points for countries with incomplete data, new years of data as they become available, and new analyses regularly. We used the index to examine the impact of the Great Recession on young people in different countries. We can track countries’ scores over time to see trends and major changes caused by policies and external shocks. It’s very useful to have a measurement for how young people are doing on the labor market, not just whether or not they are unemployed.